- A ROOM FULL OF PICTURES

- Posts

- ◉ 027 | Roko’s Flowers

◉ 027 | Roko’s Flowers

Sunlight wrapped in denim

April 2003.

For weeks,

daylight was a rumour.

I hung in the dark,

pressed between other jackets,

the air thick

with dust and memory.

Sometimes Anton opened the wardrobe—

a brief flash of light,

his hand reaching for something lighter.

Then darkness again.

The sound of the city

muffled behind wood.

By the end of the month,

there was no room left for me.

Too hot for spring,

the last Zagreb winter

still stitched into my seams.

Anton folded me carefully

and slid me into a plastic bag.

He was sending me to Split,

to his parents’ place.

Not spacious,

but bigger than this one.

Roko waited outside the university.

Anton handed me over

in a red-and-green Konzum bag.

They said a few words,

laughed quietly,

and we left.

Roko was sunlight

wrapped in denim—

an easy smile,

hair like a lion’s mane.

On the tram,

I felt the rhythm of the tracks,

his foot tapping to a song

only he could hear.

He took me to his apartment,

then later that night

we boarded the bus to Split.

Roko squashed me

into the overhead compartment.

I thought Anton’s wardrobe was tight.

It was pitch-dark—

plastic, thin air, my own heat.

Claustrophobia rose,

so I started breathing

the way I’d once heard on the radio:

inhale,

hold and whisper I am hot,

exhale—

repeat three times.

I felt better.

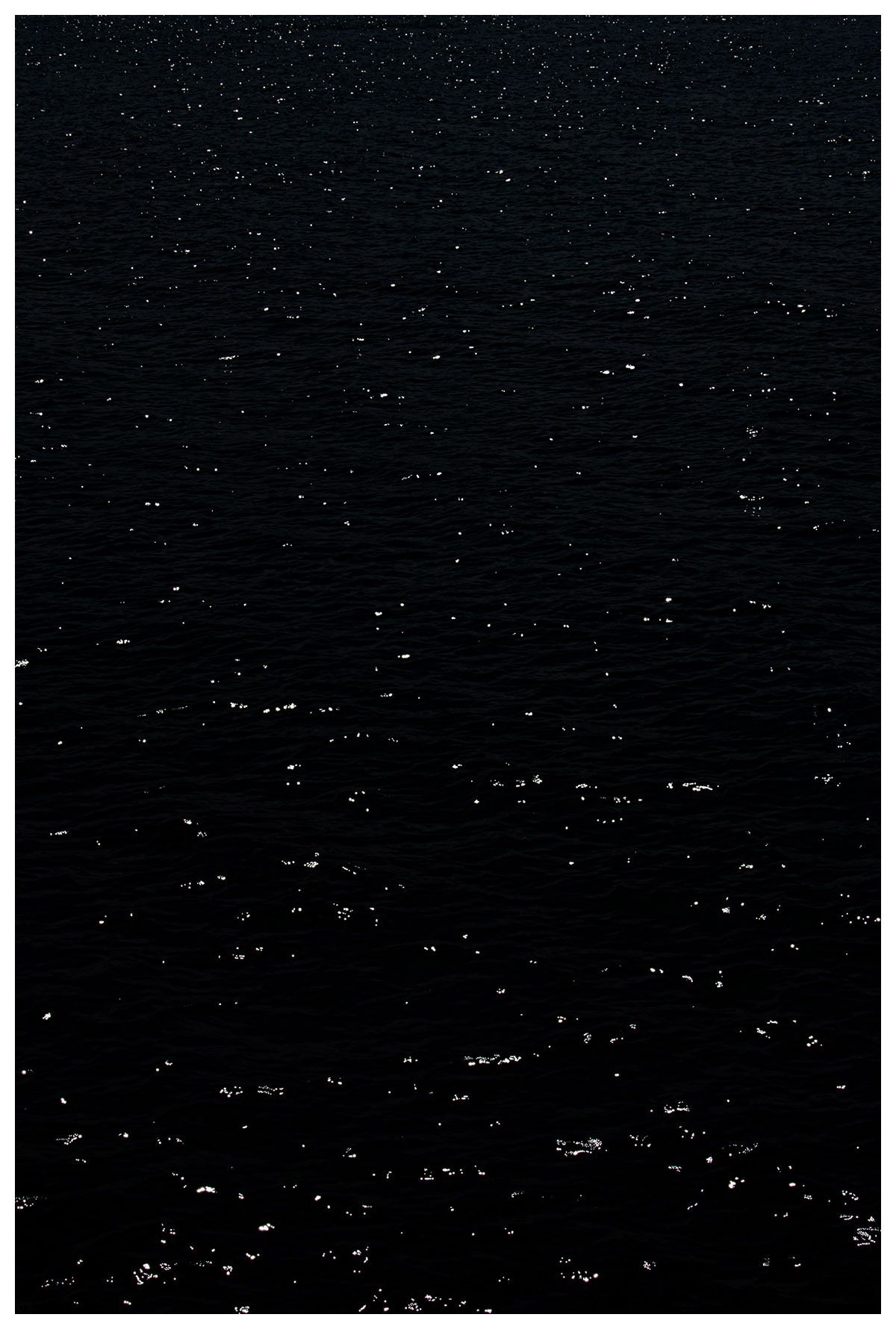

Somewhere along the highway,

I found a tear in the bag.

I watched the night roll by—

highway lights bending,

faces asleep against glass,

a kid’s reflection

shimmering in the window

beside his.

I fell asleep.

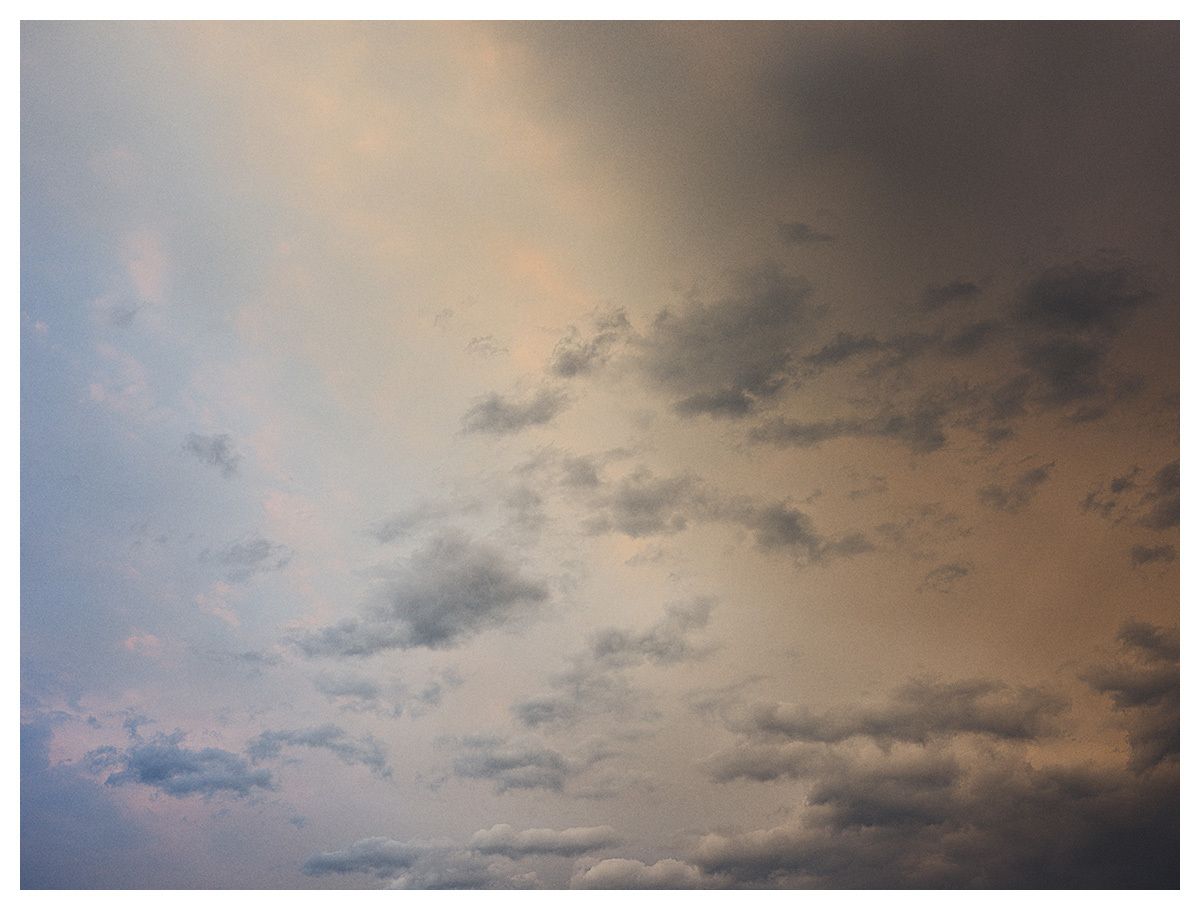

At dawn,

the red side of the bag glowed

with the first light.

It looked like the world was on fire.

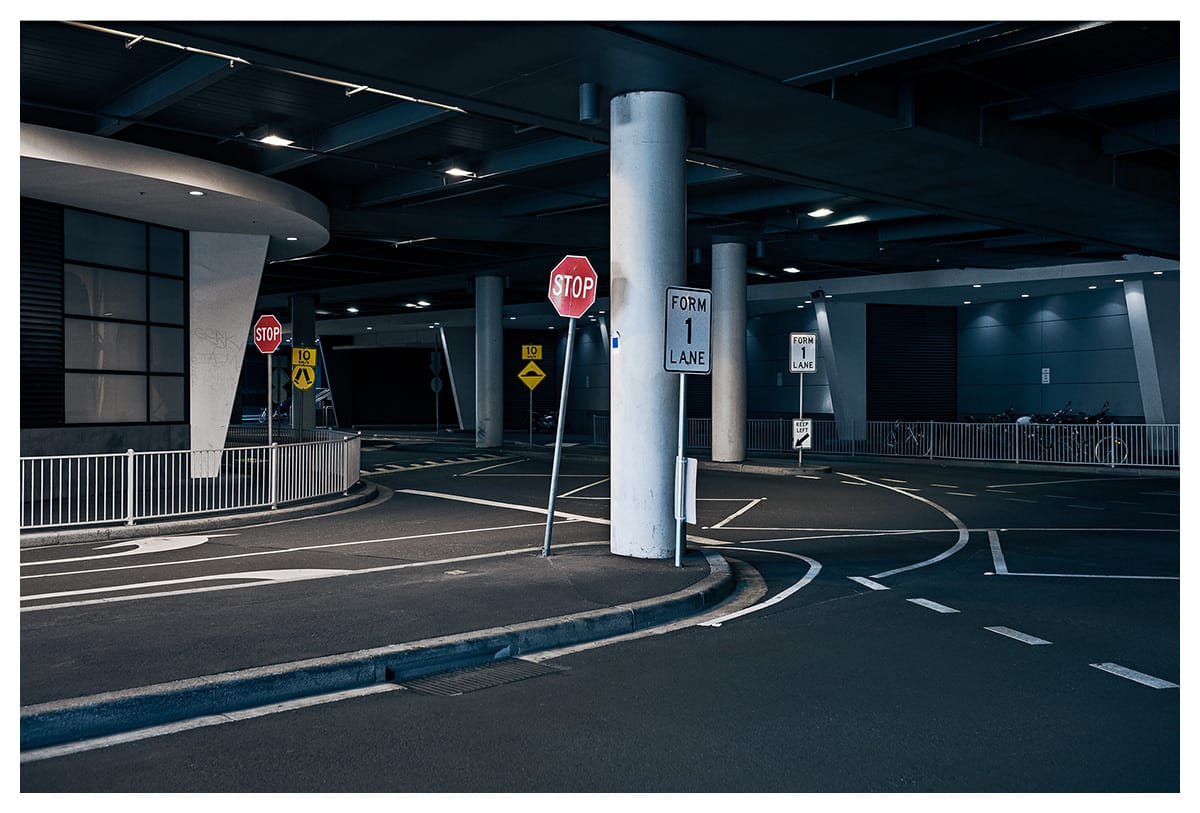

We arrived in Split.

Roko waved to his dad—

Neno was waiting in a white van

parked in the No Parking zone.

We climbed in,

and they hugged.

Roko pushed me down

between his seat

and the gear stick—

tight again,

plastic creaking,

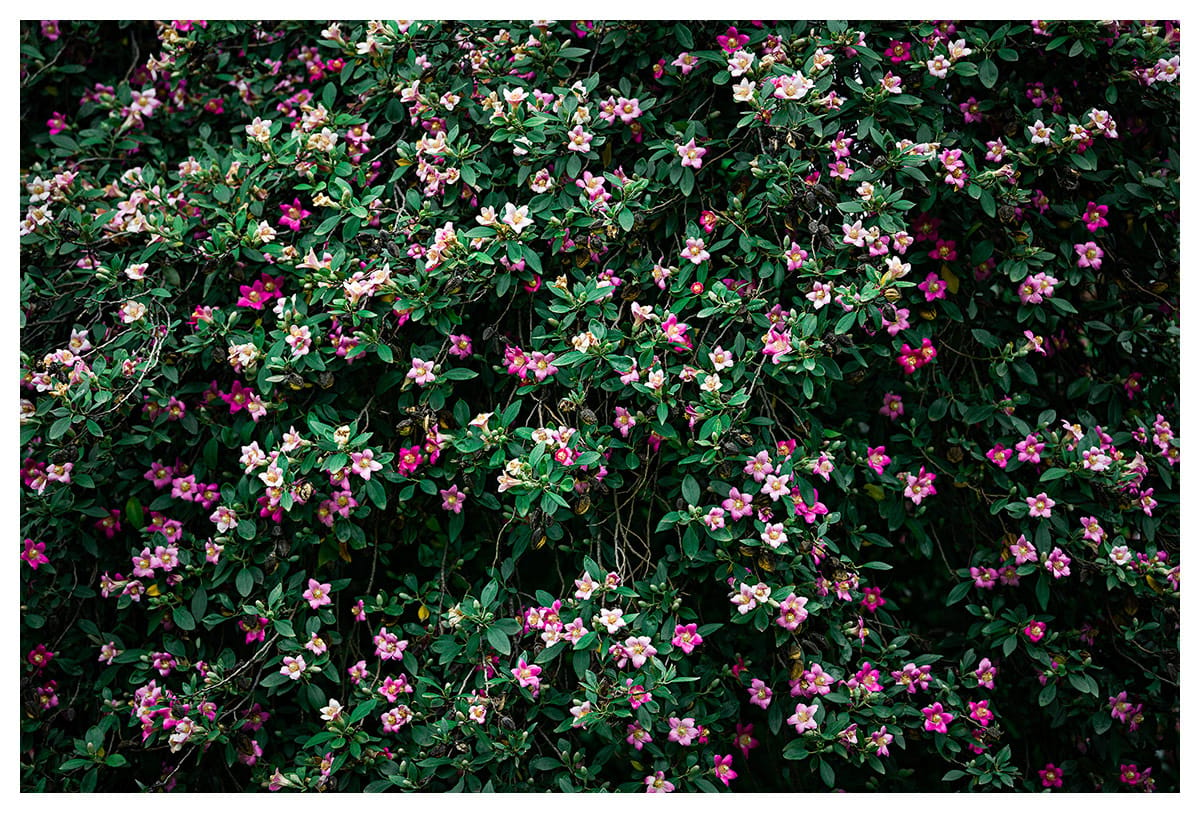

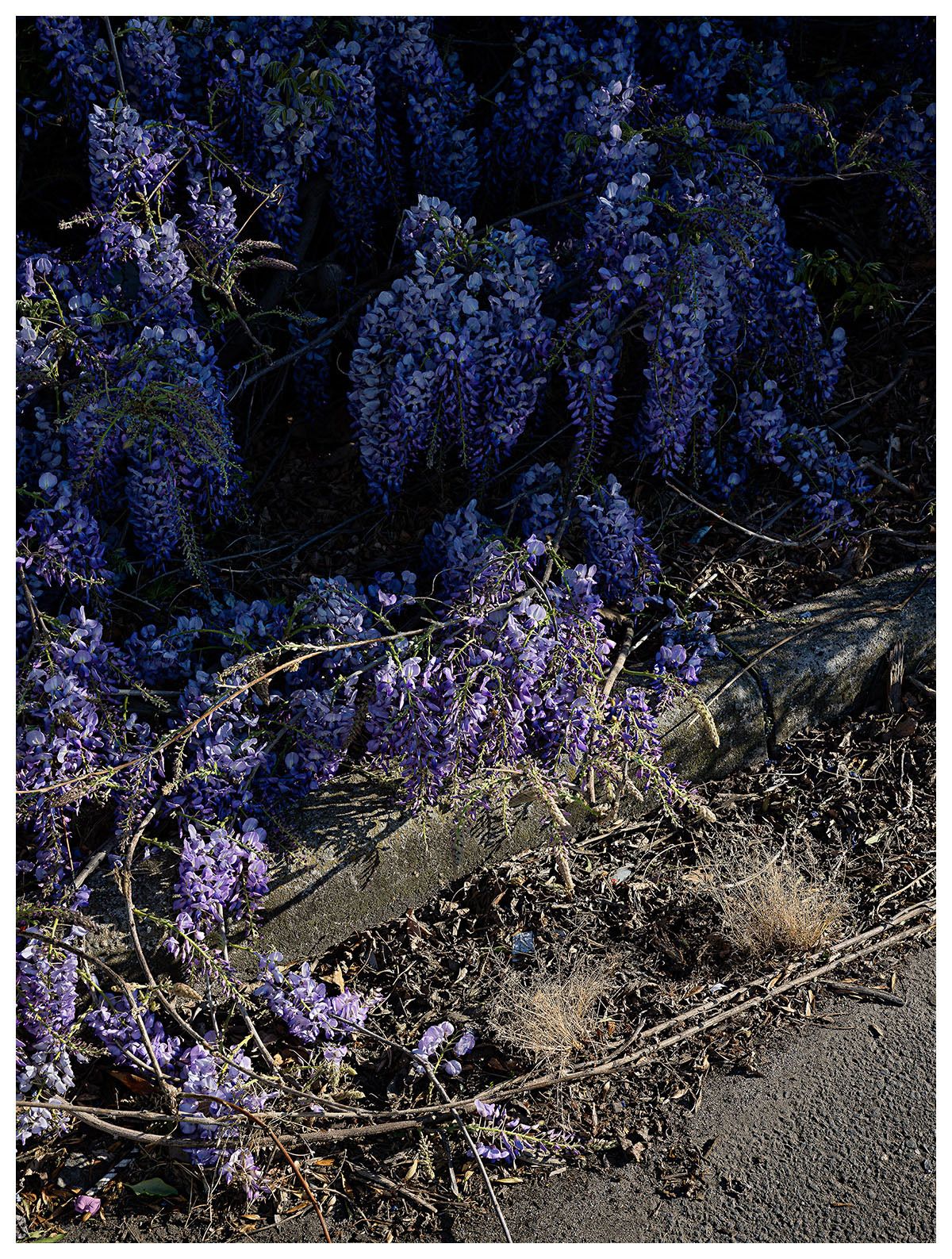

the smell of flowers thick.

Neno was a driver—

he delivered flowers

to flower shops.

We arrived at Roko’s family home.

He dropped me behind the couch,

still in the bag.

From the kitchen

came plates and low voices.

They should have been a family of six.

Only four sat at the table.

Roko’s twin brother

died at birth.

People still whispered

about the strange shadow

that follows the one who survives.

The second brother was only three

when he fell from a boat near Brač.

His grandfather turned the boat,

but the sea had already taken him.

Now there was Roko

and the youngest, Damir.

Marlena, his mother—

a nurse, steady, bright,

the kind of woman

who holds everyone else together.

Neno, on the other hand,

a wreck.

He drank.

A lot.

That night,

Roko went out

with his girlfriend and friends,

to dance,

to be twenty-one,

to be alive.

On their way home,

a man in a Yugo,

too drunk to notice the Give Way sign,

cut across the road and

slammed into a Fiat Punto.

The Punto spun,

and Roko—

just stepping onto the crossing

at Gundulićeva and Starčevićeva—

was hit.

He was taken to hospital

and died there,

in the early hours of Sunday.

I never saw him again.

A few days later,

on the day of the funeral,

Marlena handed me

to Anton’s aunty

when she came

to pay her respects.

I stayed quiet in the bag,

still warm

with the scent of flowers

from the van.

The same van

that once carried flowers

for weddings and baptisms

carried funeral flowers to the cemetery

later that day.

Roko’s flowers.

When I start to complain about anything, really,

I remember the Dvornik family—

who buried three of their four sons.

In memory of Roko Dvornik.

Pictures and Words by Anton